Have you ever wondered about mining? How and why we mine and what happens to a mine when the valuable minerals that it contains are depleted?

Did you know that if something can’t be grown then it comes from mining? Mining is an essential industry that provides the raw materials necessary to many of the goods and services that we use we use every day, including concrete and asphalt used to create roads and buildings; stainless steel used in construction, transportation and medicine; electronics such as computers and smart phones; and renewable energy technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines and batteries, important to the transition to a low carbon economy.

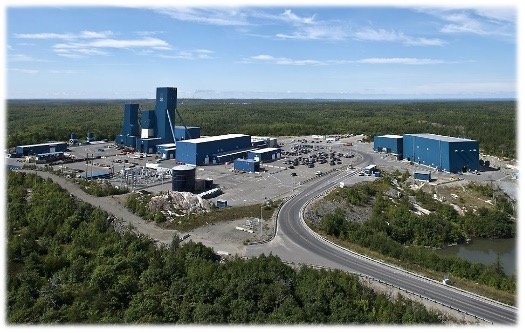

A surface mine in Ontario

Mining Matters Logo

Mining is the process of removing minerals, metals or other geological materials from the Earth’s crust. Reclamation is the process of restoring land that has been affected by mining. It is an important part of the mining cycle, a sequence of four stages that represents the “life” of a mineral deposit. The stages of the mining cycle follow an order and include exploration, which involves searching for minerals and evaluating a mineral discovery; development, which involves constructing a mine; mining and processing which is operating the mine and creating a mineral product; and the final stage which involves closing or decommissioning the mine, and reclaiming the lands disturbed by the mining process.

Reclamation, or rehabilitation as it is defined in law, is the process of restoring the lands of a mine site to their former use or condition or making them suitable for a different use. Mining activities can have impacts to the surrounding environment, affecting vegetation, soils, wildlife, and the quality of air, and ground and surface water. These effects can pose hazards to public health and safety. As a result, all land affected by mining must be rehabilitated. The goals of rehabilitation are critical and include minimizing risks to human health and safety and the environment; and achieving a productive after use for a site. Rehabilitation rules, practices, and requirements are set by the Province of Ontario and differ depending on whether an operation is an underground or surface mine. Underground operations include mined–out voids and rocks structures that must be stabilized, along with any openings to the surface must be covered. All mining operations must rehabilitate tailings, the waste materials that remain after the valuable minerals have been extracted and are typically stored on the mine lands, and revegetate lands.

Rehabilitation is defined and described in a Closure Plan, a requirement under the Ontario Mining Act. A Closure Plan is a mine site specific, legal document that outlines all of the actions to which a mining company commits in order to rehabilitate a mine during and at the end of its operation. Indigenous consultation is a requirement of the closure planning process. Local communities and the general public can play a role in the development of a Closure Plan, at the outset of the process, when it has been finalized and amended. Companies are also required to provide financial assurance to the Province, equal to the estimated cost of rehabilitation of the mine, as part of closure planning. You might be surprised to learn that Closure Plans and Financial Assurance must be in place before a mine is able to start operating! They are required as part of an extensive permitting process. Progressive rehabilitation occurs while the operation of a mine is still “in progress.” It can involve the revegetation of mined out areas, the revegetation of dry tailings and waste rock, the rock that is removed in the mining process to provide access to the ore but does not undergo any further processing, and the removal of buildings that are no longer in use.

When a mine is no longer operating, the closure process can start. First, the mine’s infrastructure and facilities, including buildings, roads, and equipment are removed from the site. Then, the reclamation of vegetation, soil cover materials, surface water and waste rock takes place. This involves reshaping lands, restoring topsoil, and planting native vegetation, including grasses, trees, or ground cover. How tailings are reclaimed depends on whether they are inert (chemically inactive) or reactive (can react with other substances). Inert tailings can be rehabilitated using a vegetative cover. Materials called amendments are applied to cover the tailings before vegetation is planted in an effort to improve outcomes. Reactive tailings can pose a risk to the environment. Reclaiming these types of tailings can involve covering them with water or earth materials, preventing the tailings from oxidizing and mobilizing toxic metals as a result. At some operations in Ontario, thickened tailings are used to backfill underground mines. This is a sustainable way in which to reduce water use on site and stabilize reactive tailings.

When the reclamation work is complete, the site is inspected by a government representative to ensure that commitments made in the Closure Plan are met and the financial assurance is returned to the mining company.

In some situations reclamation becomes the responsibility of the Province. This can be the case for mines in operation before legal requirements for reclamation were in place. This is the case with the Kam Kotia site, located near Timmins Ontario. Operating for 30 years, the mine produced copper and zinc but did not undertake any land reclamation. Exposed reactive tailings and waste rock created acidic run-off that impacted the creeks and rivers located in close proximity to the mine. The lands and mineral rights were forfeited to the Crown in the 1980s, meaning that the rehabilitation became the responsibility of the government.

Involving multiple projects and tremendous costs, rehabilitation work ultimately reduced the footprint of the Kam Kotia Mine from 600 million tonnes of unmanaged, acid generating tailings originally covering a 500-hectare site to an approximately 200 hectares of covered, sealed and controlled tailings, resulting in a 60 per cent improvement. The environmental conditions have significantly improved and can now sustain vegetation, control erosion, reduce contamination and support wildlife.

Mine reclamation and rehabilitation practices have evolved over time. Research and innovation have led to advancements, continuous improvement, and the development of best practices. Manufactured soils are being used in reclamation. Experimentation with organic amendments like biosolids and pulp and paper mill by-products has resulted in improved establishment of vegetation at sites while also diverting waste from landfills. The initial goal of rehabilitation may have been making sites safe, and the quick establishment of vegetation in an effort to stabilize land. Now, it also focuses on sustainability and environmental management, establishing native plant communities, including boreal forest and subarctic species, the incorporation of pollinators plants, and supporting species at risk.

Research conducted on Ontario Mine Sites has focused on rehabilitating waste rock piles using manufactured soils and native plant species found in the boreal forest surrounding the operation, rehabilitating peatlands impacted by mining in the subarctic region, and applying native seed mixes to support regional biodiversity and small-scale honey production. Some underground mine sites that had become hibernacula for bats were rehabilitated using custom built structures that provided bats access to the underground while also preventing public access.

The Ontario Chapter of the Canadian Land Reclamation Association serves to highlight reclamation achievements in the province, recognize excellence in students, the mining industry and individuals who have shown outstanding achievement in the practice of mine reclamation through the Tom Peters Memorial Mine Reclamation Student and Industry Awards and the Dr. Jack Winch Memorial Scholarship. https://www.clra.ca/ontario-chapter

Lesley is the Manager, Education and Outreach Programs with Mining Matters, a partner organization of the APGO Education Foundation. She is an Earth Sciences Specialist, Educator and Science Communicator with experience in the Natural Resources Sector, and in Higher and Informal Education. She has worked as a practitioner, in the stone, sand and gravel industry; in Government Relations and as a mining and environment policy analyst for the Ontario mining sector; in post-secondary education in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Instructional Development, Course Design and as a Sessional Lecturer; and in Informal Education, providing Earth Science and mineral resources education to students and the public, and professional learning programs to Educators.

Lesley is an active member of the national Earth Science Education and Outreach community and is currently serving a term as Co-Chair of the EdGEO National Committee. Lesley serves as a Director for Ontario Chapter of the Canadian Land Reclamation Association (CLRA). The Ontario CLRA Chapter hosts the annual Ontario Mine Reclamation Symposium and Field Trip and co-hosts the Sudbury Mining and Environment Conference. Lesley is a former member of the Ontario Biodiversity Council (2010-2016).

Lesley has Undergraduate and Graduate Degrees in Earth Sciences, from the University of Guelph and an Ontario Master Naturalist Certificate from Lakehead University.