When you hear the term “Ring of Fire,” you might think of Johnny Cash’s famous song by that name. Or, if you remember grade school geography, you might think of the Pacific Ring of Fire—an area of high volcanic activity that surrounds the Pacific Ocean like a ring. But you probably haven’t heard of the third use of the phrase—Ontario’s Ring of Fire. In Ontario, the Ring of Fire is an area of 5000 square kilometres located approximately 400km north of Thunder Bay where there are significant mineral deposits. It’s called the Ring of Fire for two reasons. #1: If you look at a magnetic map of the area, there is a clearly delineated arc of responses. And #2: The founder of Noront, the mining company who first discovered the minerals in the area, was a huge fan of Johnny Cash.

The Ring of Fire is made up of shared lands governed by 9 different First Nations. In recent news, the Ring of Fire has come to public attention due to concern from First Nations communities who are opposing the development of mines in the area and criticizing the government’s insufficient involvement with Indigenous communities in decision making processes.

Let’s take a step back and look at why the Ring of Fire is geologically and environmentally important. Geologically, the Ring of Fire is an arcuate belt of Archean (approx. 2,750 MA) mafic and ultramafic rocks surrounding an intrusion of granodiorite. Based on exploration to date, the area is rich in deposits of important metals such as nickel, chromium, copper, zinc, and platinum.

Since the Ring of Fire’s mineral deposits were discovered in 2007, mining companies have been eager to start developing mines in the area. Some of these deposits would likely be amenable to profitable underground mining (e.g., Noront’s Eagle’s Nest), but most of the chromite deposits discovered to date would require open-pit mining to extract them. There have been estimates of the total in-situ value of the Ring of Fire deposits ranging from $30 billion to $60 billion. However, the investment and costs required to extract them may reach similar levels, such that the actual economics of mining some of these minerals in the area remain to be established.

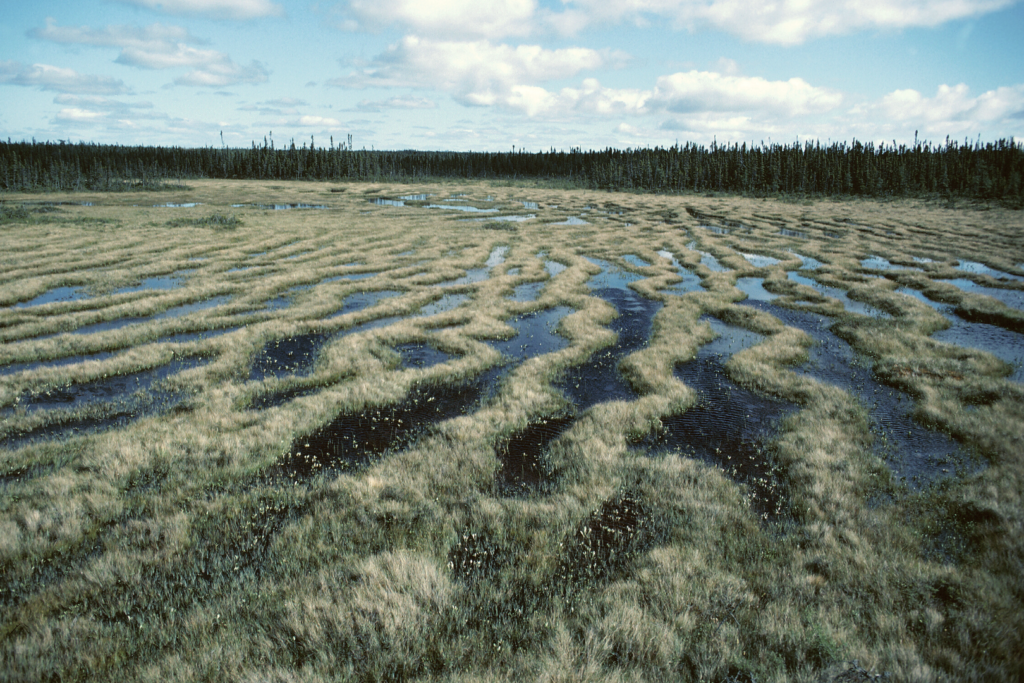

Ecologically, the Ring of Fire is situated in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, which is the largest peatland in North America. Peatlands are waterlogged ecosystems where organic matter never fully decomposes, leading to the buildup of peat. This means that peatlands store large amounts of carbon from partially decomposed organic matter. The peatlands also absorb carbon dioxide from the air, acting as a filter for CO2. Peatlands are therefore important in storing and retaining carbon to mitigate the effects of climate change. As several Indigenous Chiefs have noted, disturbing these peatlands would release their stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Since carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, the release of CO2 would go against the promises made by the Canadian Government at the Paris Accord to mitigate climate change.

The potential impacts upon the environment from mining in the Ring of Fire are substantial, particularly if it was proposed to extract chromite (the chromium mineral) by open-pit methods. Not only would that process disturb the peatlands, potentially releasing stored carbon from the peatlands, but surface disposal of mine waste and tailings would (at least in part) be deposited on top of the peat.

Indigenous communities have also emphasized the potential negative impacts on surface and groundwater from mining, as several First Nations live directly downstream from the Ring of Fire and would be negatively affected by any toxic runoff or damage to the rivers.

The Canadian and Provincial governments have made a goal to invest in the production of electric cars to decrease Canada’s emissions from gas- and diesel-powered engines. The mineral deposits in the Ring of Fire contain nickel and copper, essential minerals for building electric car batteries. In March 2022 the Provincial government released a plan to build electric cars from start to finish in Ontario and has stated that this would require minerals to be mined in Ontario as a first step along the production line. Ontario already produces both nickel and copper from existing mines in the province, so new developments in the Ring of Fire would be complementary to those currently operating and could add significantly to the resources available for incorporation in electric vehicles as their production is ramped up over the next few years.

Opening mines in the Ring of Fire could be a great boost for Ontario’s economy, as they would generate many job opportunities for local communities. Several of the communities surrounding the Ring of Fire are not currently accessible by road, so building infrastructure to support the mines would connect these communities to Ontario’s provincial highway system and allow electricity to be delivered by powerlines rather than diesel generators, thus reducing the carbon footprint of those communities.

There are many different factors to consider when deciding whether mining developments in the Ring of Fire should go forward. Included amongst these is weighing the cost of releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere with the potential decrease of released carbon from electric vehicles. Additionally, the potential impact on the watershed or the increase in jobs for First Nation communities should be considered. These factors are some of the issues that comprehensive Environmental Assessments are designed to evaluate thoroughly.

One of the major considerations in any new mining development proposal is the duty to consult and engage with local and affected communities. In this case there is strong opposition from some local Indigenous communities. In early January 2021, groups from the 9 affected First Nation communities met with the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault to discuss the upcoming Regional Impact Assessment that is planned for the area. The goal of the RIA is to quantify the extent of the ecological impact of mining on the Ring of Fire.

Soon after the meeting, chiefs from Attawapiskat, Eabametoong, Kashechewan Cree, Fort Albany, and Neskantaga First Nations sent a letter to Steven Guilbeault outlining their opposition to the planned RIA. They wrote that what the Canadian and Ontario government plans to do is “far from proper or safe” and that the draft of the Terms of Reference for the Regional Impact Assessment is “narrow in geographic and activity scope, and excludes us Indigenous peoples from all but token roles.”

Guilbeault replied to the letter on January 28th, but it seems that the First Nations were not satisfied with his response. Three of the nations declared a moratorium on development in the Ring of Fire on April 1, 2021. Kate Kempton, a lawyer and spokesperson for Attawapiskat said that “This is about trying to ensure that if anything happens there, it is done through a proper, full, comprehensive [RIA] and planning process with First Nations at the center of it, rather than at the periphery of it, which is what Canada’s proposing to do.”

However, not all local First Nations groups oppose the development. Marten Falls First Nation became a Noront shareholder when their chief Bruce Achneepineskum signed an Exploration and Pre-Development Agreement in 2017. They continue to support the mine exploration and Regional Assessment despite the disagreement of other chiefs.

Additionally, Marten Falls and Webequie First Nations signed an agreement in 2020 with Premier Doug Ford to start development of an all-season road travelling north/south to allow access to the Ring of Fire and nearby communities. This is the first step toward building infrastructure that would allow for mining to take place and will be subject to an RIA.

It’s now 2022, and progress on the Ring of Fire seems to be inching forward, however slowly. What will come next for Ontario? Will the current government decide to continue with the Regional Impact Assessment despite the backlash? Or, as requested, will they scrap the RIA and start fresh with input from local First Nations? Beyond that, is the risk of releasing carbon into the air worth the financial and industrial benefits? Could environmental mitigation efforts and First Nation leadership be enough to safely extract the minerals from the delicate peatlands?

Only time will tell.

Veronica Klassen is the Manager of the Foundation’s blog – Beneath Your Feet: A Geoscience Blog. She studied Arts and Science at McMaster University with a minor in Earth Science and has a masters in Science Communication from Laurentian University. She is passionate about making science accessible and engaging to the public.