This article takes you to a small but fascinating area just north of Peterborough, Ontario. The area has a wonderful variety of geological features that formed from a billion to thousands of years ago. If you ever wondered what you were looking at on a drive in the area, read on!

The Peterborough area is a great place to take a trip along the geologic timescale. We’ll go way back in time to about a billion years ago and move up to more recent times a few thousand years ago. First, we’ll look at some illustrations and maps to better understand what went on during that vast stretch of time. Then, we’ll look at some interesting photos of what you will see yourself when you go for a drive in the area.

And by the way, the drive from Peterborough and back is less than 100 km!

Illustrations and Maps

Peterborough sits on the southern edge of a unique ecosystem transition region called The Land Between. The whole of The Land Between is outlined below with a white boundary. The highland area to the north is called the Algonquin Highlands or Dome and the lowland area to the south is called the Great Lakes Lowland. The Land Between straddles the two, hence the name!

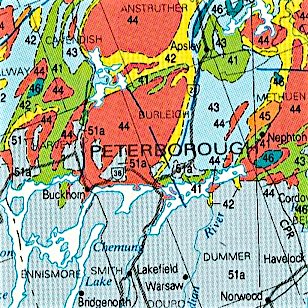

Before we go on a small road trip, let’s take a look at some maps. The first one is a bedrock geology map. Bedrock is the rock that’s underneath soil. If there’s no soil covering the rock, then it’s called a bedrock outcrop. Something I love about the area just north of Peterborough is that there are lots of different kinds of bedrock outcrops.

There are basically three types of rock on the surface of the Earth – igneous from magma, metamorphic from high heat and pressure transformations, and sedimentary from eroded fragments and near-surface chemical transformations.

The multi-coloured area at the top of the map is Precambrian metamorphic and igneous rock of the Canadian Shield. This rock formed about a billion years ago during a mountain-building event like the one that is creating the Himalaya Mountains. The mountain-building was part of the formation of an ancient supercontinent called Rodinia.

What we see today at the top of the map is the ancient core of the mountains after thousands of metres of rock were eroded off. This might seem far-fetched, but there’s a lot that can happen over several tens of millions of years!

The blue area at the bottom of the map is Paleozoic limestone and shale underneath the Great Lakes Lowland. These are Paleozoic sedimentary rocks that formed a few hundred million years ago when Ontario was south of the Equator under a warm inland sea that was a few hundred metres deep.

It’s perhaps hard to imagine what these shallow seas looked like because there’s nothing in the world like them today. Here’s what a globe of the Earth probably looked like about 450 million years ago during the Paleozoic.

What you see is the result of plate tectonics and the constant motion of the Earth’s continental and oceanic crusts driven by the heat coming from the Earth’s core. If you can wait a billion years, you don’t have to travel to see the world. You just have to sit tight and wait for plate tectonics to take you everywhere!

The next set of geology features in the area was left from the most recent ice age, called the Pleistocene. It’s called the most recent ice age because the rock record tells us there have been at least a few global ice ages over the past several hundred million years. Some geologists think that maybe two or three of them in the ancient past were so big that the Earth looked like a snowball from outer space. In between ice ages there have been warmer “greenhouse” periods.

During the Pleistocene, glaciers 1-2 kilometres thick advanced and retreated several times over northern North America. Most of the glacial ice retreated approximately 12,000 to 10,000 years ago. If Earth’s geologic timespan of 4.6 billion years was shrunk down to 24 hours, the ice melted less than a second ago!

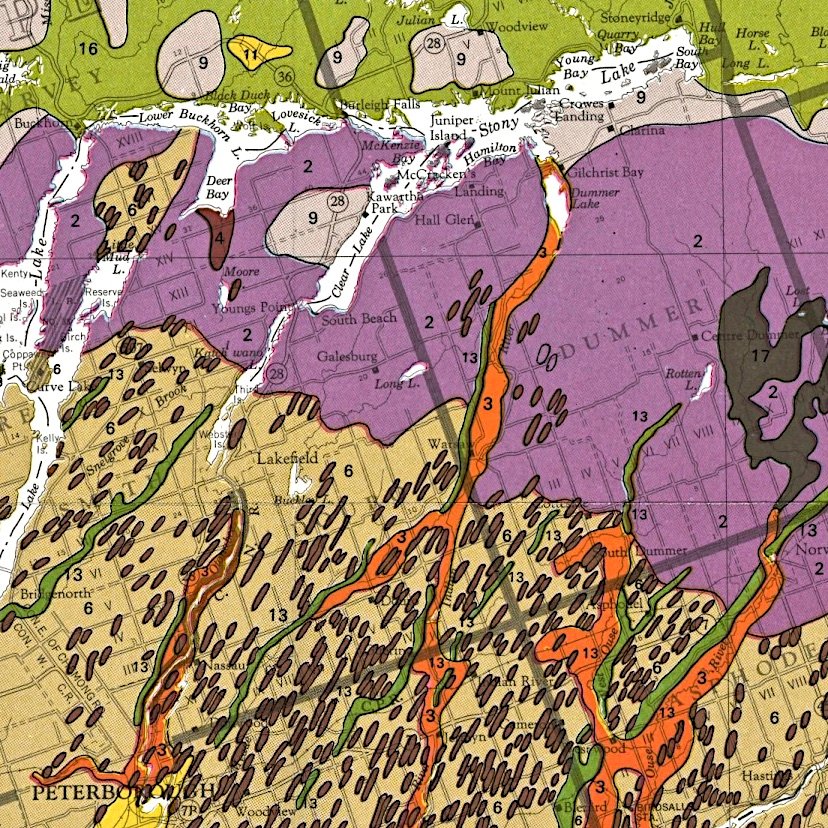

The map below shows glacial features that were left in the area.

The area at the top above the Kawartha Lakes including the green area is bare rock and shallow soils on the Canadian Shield. The purple area till of the Dummer Moraine. Orange “ribbons” are spillways created when the ice melted and dark green ribbons are river deposits called eskers formed under the melting glaciers. Eskers make great sand and gravel pits. The dark brown blobs are drumlins and part of the famous Peterborough Drumlin Field.

But, enough of maps. Let’s take a drive and see some of the geology features that this article has mentioned so far.

Road Trip

Starting near the bottom of the timescale and working our way up to younger ages, we’re going to make stops at Gilchrist Bay, Galesburg, Lakefield and Warsaw Caves Conservation Area.

Our first stop is at Gilchrist Bay on the south shore of Stoney Lake. The beautiful rocks shown in the photo below are a mixture of metamorphic and igneous rocks that formed in the core of an ancient mountain range a billion years ago.

The dark rock is metamorphic gneiss formed by tremendous heat, pressure and fluid movement. The pink rock is igneous granite that cooled after magma intruded and cut across the older metamorphic gneiss. The slow cooling of the granite formed large grains or crystals that you can see without a magnifying glass. This bedrock outcrop also has one of my favourite rocks called migmatite, which is a mixture of metamorphic and igneous rock.

Here is a close-up of a granitic vein. The pink grains are feldspar, and the clear grains are quartz. You need a magnifying glass to see the small grains in the dark metamorphic rock on either side of the vein.

Our next stop is at a place called Galesburg, about half-way between Lakefield and Warsaw Caves. Although there are no signs marking Galesburg, it is locally famous to geologists for having a bedrock outcrop of what is called the Great Unconformity.

Unconformities are breaks or surfaces between rock formations that represent time gaps in the geologic record. The time gap at Galesburg between the Precambrian Shield rocks on the bottom and the Paleozoic limestone rocks on top is about 450 to 500 million years.

Similar time gaps are found in the rock record in several places in the world, which is why it is called the Great Unconformity. Some geoscientists think it was caused when Earth was almost completely frozen near the end of Precambrian. Others think that it was caused by erosion of the ancient supercontinent Rodinia. There is still lots to learn about the ancient life of our planet.

Our third road stop is at Lakefield, which is surrounded by Paleozoic limestone and shale in the Great Lakes Lowland. The photo below shows thin shaly limestone layers or beds. You can see several outcrops like this along the Otonabee River between Peterborough and Lakefield.

Limestone in the Lakefield area has lots of fossils. Here are some examples.

The fossils come from invertebrate animals that lived on the bottom of the Paleozoic shallow seas. They were the highest life forms at the time, and this part of the Paleozoic is called the Age of Invertebrates. The next age was the Age of Fishes. There aren’t any fish fossils in the Peterborough area because the Peterborough sedimentary rocks are too old.

Our final road trip stop is at Warsaw Caves Conservation Area, east of Lakefield and south of Gilchrist Bay. Although famous for its limestone “caves”, the area has some wonderful Pleistocene glacial features. Otonabee Conservation has a cave brochure and a park features map on their website here.

The photo below shows a “pothole” that was ground into the limestone bedrock by a hard pebble of Canadian shield rock swirling around in ice melt water.

When the last glacier in the area finally melted, there was so much water that it carved a beautiful deep gorge at Warsaw Caves. It’s a great spot to sit for a while. You wouldn’t know that you are in Peterborough County because there is no other scene like it in the area.

And that concludes our trip along the geologic timescale in a small but fascinating area just north of Peterborough, Ontario.

We went from a billion to thousands of years ago, saw all three of the major rock types, saw the core of an ancient mountain range like today’s Himalayas, saw a time gap in the rock record of about a half billion years, saw a time when Toronto was south of the Equator and the highest life forms were invertebrates, and saw some distinctive features from the last time when the area was glaciated.

The whole trip can be made in less than 100 km starting and ending from Peterborough. There is nowhere else like this in Ontario.

Get out, explore and enjoy!

Ken Lyon, M.Sc., P.Geo.Ken is a semi-retired contaminated sites hydrogeologist, recreational geologist, and instructor at Trent University where he is currently teaching a course on environmental geology. Ken has recently compiled an annotated list of information resources for exploring the geology of Ontario. You don’t need to know anything about geology to get started. If you would like a free copy, send him an email at kenlyongeo@gmail.com.