What do geoscience and video games have in common? More than you might think.

Geoscience is key to understanding our world and addressing environmental crises. Despite this, geoscience programs continue to see a decline in numbers, and getting youth excited by and interested in geoscience is vital to the continuation of the field.

In Canada, youth spend an average of 7.9 hours per week playing video games. Video games are designed to entertain and often provide immediate rewards. In her 2010 TedTalk “Gaming can make a better world,” Jane McGonigal argues that self-learning from video games is just as important as formal education. By the time the average person in a country with a strong gaming culture turns 21, they will have spent 10,000 hours playing video games (Carnegie Mellon University). That same youth will have spent 10,080 hours in school from grade 5-12. “We have an entire parallel track of education going on, where young people are learning as much about what it takes to be a good gamer as they’re learning about everything else,” Jane states.

When gaming, youth are developing skills, adapting to changing environments, problem solving, and taking in new information. Judy Willis (2007) states that, “when students are engaged and motivated and feel minimal stress, information flows freely through the affective filter in the amygdala and they achieve higher levels of cognition, make connections, and experience “aha” moments. Such learning comes not from quiet classrooms and directed lectures, but from classrooms with an atmosphere of exuberant discovery.” I would argue that this theory applies not just in the classroom, but in informal settings including while youth are playing video games.

Research shows that there are two main types of self-learning: tangential learning and incidental learning. Tangential learning is when someone consciously educates themselves on a topic they have been exposed to and in which they have interest. Incidental learning is less conscious and occurs through engaging in activities and tasks that promote learning. Video games are good at both of these types of self-learning.

So, youth are learning from video games, but what exactly are they learning?

There are two main types of video games: educational and entertainment. Educational, also called serious, games are designed with education as a priority. Often, these types of games sacrifice entertainment and end up being somewhat less engaging than off-the-shelf games. Popular off-the-shelf games usually use larger-than-life experiences or fantastical and magical environments to entertain players. As far as science communication is concerned, both educational and entertainment-focused games have the potential to teach science. However, it has been found that youth playing educational games tend to get bored easily and lose focus, which undermines some of their effectiveness (E. G. McGowan and J. P. Scarlett, 2021).

McGowan and Scarlett (2021) looked at the representation of volcanoes in off-the-shelf, or entertainment-focused, video games. They analyzed 11 of the most popular video games that contain elements of volcanism. They looked at what types of volcanic hazards were represented and whether or not they were scientifically accurate.

They chose to study volcanoes because they are a common geological phenomena that are often used in video games either as part of the background landscape or to provide a dangerous challenge. Volcanoes in real life can of course produce fascinating and beautiful landscapes as well as deadly effects such as lava flows, toxic ash fall, volcanic gases, lahars, pyroclastic flows, lava bombs, and more. This makes volcanoes a good challenge for players and is why they are often included in video games. The researchers wanted to find out if volcanoes were being portrayed with scientific accuracy.

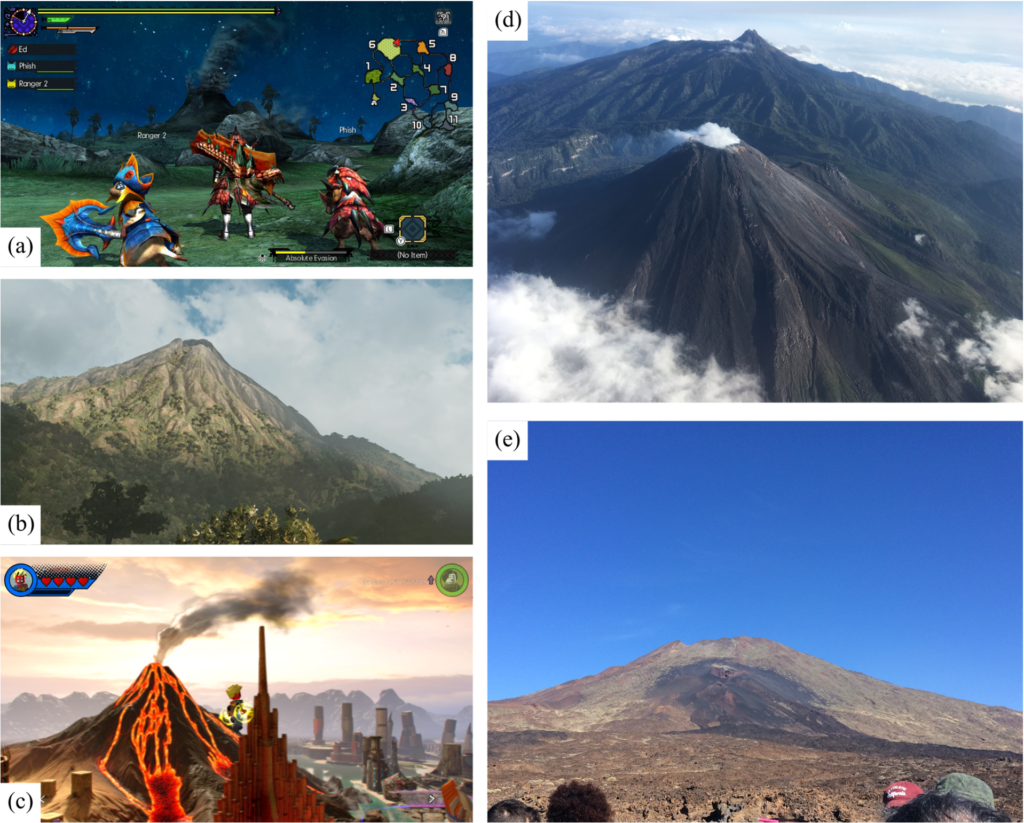

Figure 1. Stratovolcanoes in Monster Hunter: Generations Ultimate © Capcom (2018; a), The Shadow of the Tomb Raider © Eidos- Montréal (2018; b) and LEGO Marvel Superheroes 2 © TT Games Ltd (2017; c); aerial view of the stratovolcanoes Volcán de Colima (foreground) and Nevado de Colima (background) in Colima, Mexico (Edward McGowan, 2018; d); view of active Las Can ́adas summit from within Caldera de las Can ́adas, Tenerife (Edward McGowan, 2016; e).

They found that the video games studied all had both accurate and inaccurate features of volcanoes, with no single video game being completely inaccurate or completely accurate. This means that any video game will have some aspect that correctly represents volcanoes, and so can inform gamers via incidental or tangential learning. It also means that any video game will have some aspect that may mislead or incorrectly teach people who play them. However, since most of these inaccuracies are used for the purpose of dramatization, it’s not necessarily the case that people are mis-learning from them. After all, people are capable of distinguishing video game landscapes from real ones.

A study by Hut et al. (2019) compared how well geoscientists and non-geoscientists could determine which landscapes in a video game were accurate to reality. They found that while geoscientists could more accurately determine false from real landscapes, non-geoscientists were also able to determine the difference fairly well. They concluded that despite the minor difference, video games can still be used for tangential learning on geoscience subjects.

McGowan and Scarlett (2021) concluded that video games could be used for outreach purposes in order to spark interest and get people invested in geological phenomena that they might not otherwise be interested in. This can lead to incidental and tangential learning, since video games are engaging and exciting. Once people are interested in a topic, they are more likely to seek out more information themselves and put effort into learning, so this can lead to more geoscience education.

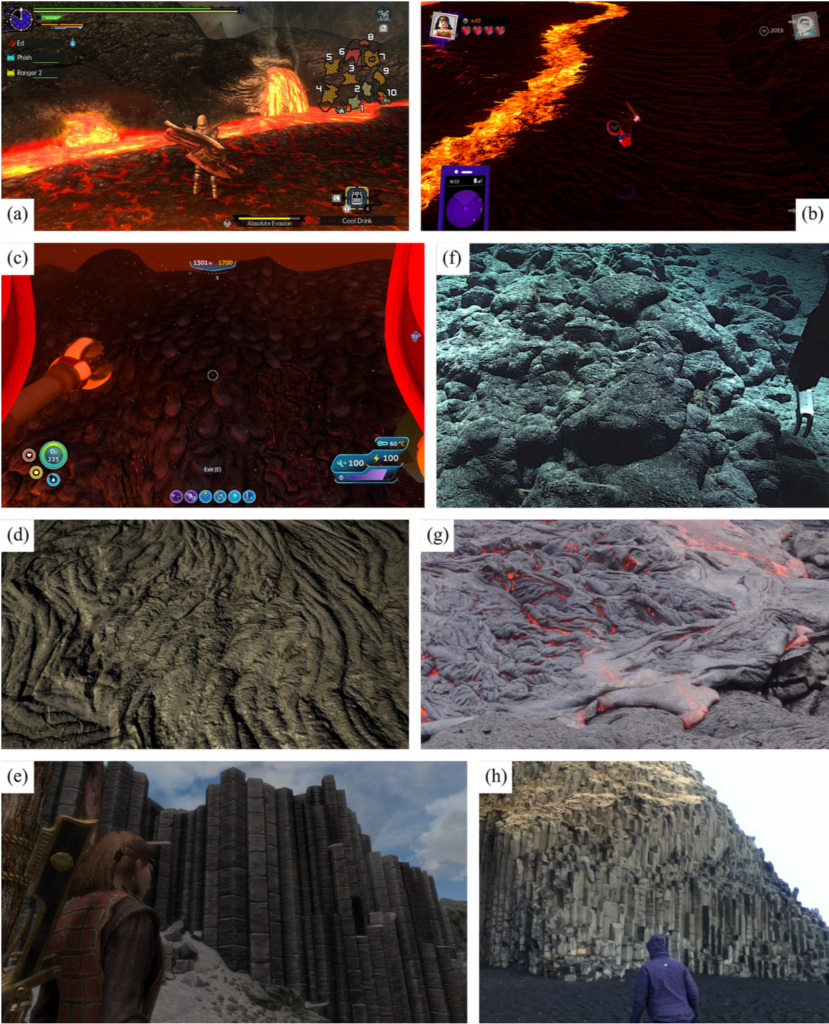

Figure 2: Lava surfaces in Monster Hunter: Generations Ultimate © Capcom (2018; a), ropey pahoehoe textures in LEGO DC Super-villains © TT Games Ltd (2018; b), pillow lavas in Subnautica © Unknown Worlds Entertainment (2018; c), more ropey pahoehoe textures in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey © Ubisoft (2018; d) and columnar textures in The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim © Bethesda Game Studios (2016; e). Real-world examples of pillow lavas (Keoea Seamount, NOAA, 2015; f), ropey pahoehoe textures (Hawaii, Lis Gallant, 2013; g) and basaltic columnar textures (Iceland, Edward McGowan, 2014; h).

We can use video games for geoscience education, but we also need gamers for the field of geoscience.

In her TedTalk, Jane McGonigal argues that gamers are learning four things while playing video games: urgent optimism, social fabric, blissful productivity, and epic meaning. Firstly, urgent optimism is the ability to act immediately to achieve a goal, with the belief that it is possible to complete. Secondly, gamers weave a tight social fabric through collaboration and competition with others. Next, gamers are experiencing blissful productivity. Video gaming is often associated negatively with laziness or lack of motivation, when in reality, gaming is productive work. It’s work that often feels more immediately rewarding than real-life work due to instant in-game rewards. Finally, epic meaning is the belief you are completing something meaningful and awe-inspiring, even if just to a fictional world.

Chris Skinner (2021), a Researcher at the Energy and Environment Institute, argues that these four qualities are vital to geoscience. Specifically, the idea of the “epic win,” as coined by McGonigal, means that gamers believe that amazing things are achievable through hard work and practice. This is important to the practice of geoscience, as geoscientists require ingenuity and problem-solving skills. Skinner says that to solve the environmental crisis, “we need geoscientists who are creative, persistent, and optimistic enough to envisage these solutions – we need super-empowered hopeful individuals – we need gamers”.

If gamers can apply the epic win mindset to environmental issues, then they can accomplish a lot simply because they believe it can be done. This mindset is in stark opposition to the eco-anxiety that is so prevalent among young people and can lead to fatigue and overwhelm. The planet needs people who are optimistic problem solvers, just as geoscience communication needs new tactics for sparking interest. Video games can help teach youth about geological concepts, spark their curiosity, and encourage tangential and incidental learning.

Next time you play a video game, consider the things you might be learning without realizing it. Consider how the game represents geological phenomena and whether or not they are accurate to reality. Think about how the epic win mindset plays a role in motivation, and how you can apply that mindset to other areas of your life. Look for the connections between the virtual world and the real one, and reflect on what gaming can teach you.

References:

TedTalk Jan McGonigal The Game That Can Give You 10 Extra Years of Life

Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World

The Impact of Educational Games on Learning Outcomes: Evidence From a Meta-Analysis

Can we teach children geology using one of the world’s most popular video games?

The average gamer plays more than one hour per day, as time spent takes centre stage

Author Veronica Klassen is the Manager of the Foundation’s blog – Beneath Your Feet: A Geoscience Blog. She studied Arts and Science at McMaster University with a minor in Earth Science and has a masters in Science Communication from Laurentian University. She is passionate about making science accessible and engaging to the public.