Geodiversity Takes Centre Stage

Paul Hubley, P.Geo.

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women merely players,

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages…

Excerpt from William Shakespeare As You Like It (spoken by Jacques)

An explosion of Homeric (epic) proportions, an estimated 13.8 billion years ago, gave rise to everything physical and chemical around us today. The blast was so great that some even postulate that the early moments of our universe even had several additional dimensions compared to those we know now. And it is all still expanding.

Physics tells us that explosions result in a release of energy–a reordering of matter. Chemistry tells us that they are the dismantling of something old and creation of something new. Clinical psychologists refer to explosions as a trauma after which a new awareness can be developed over time. Explosions have shaped our consciousness, informed our rituals, politics and religion, and are often expressed in parables or in oral tradition, theatre, poetry and popular culture. One thing is certain–as the curtain lowers in the aftermath of an explosion, things are not the same as they were.

When we examine our world on the backdrop of explosive events, we judge some events to be acceptable or even good, whereas some we reject as bad. Some explosions play a small part in our history while others occupy centre stage. Natural or manmade, terrible or wonderful, detonation or no detonation, explosions have always been a fascination to many, including geoscientists. Whether it be meteorite strikes resulting in extinction events, or tritium detection from atomic bombs being tracked in groundwater for age-dating, some geoscientists dedicate their careers to understanding explosive events.

In an excerpt of As You Like It, Shakespeare introduced seven Acts for seven ages, beginning with the iconic line “All the World’s a Stage.”

Classical Latin explōdō means “to hiss a bad actor off the stage,” or “to drive an actor off the stage by making noise,” from ex- (“out“) + plaudō (“to clap; to applaud“), hence meaning “to drive out” or “to reject.” The modern meaning developed later. In Shakespeare’s time, just as with the ancient Greeks, men were the only ones allowed to be theatre actors–fortunately in theatre we’ve generally developed a more sensible sense of diversity since that time, and benefited greatly from it.

Shakespeare described seven ages of a man’s life, from young to old. Our play also has seven Acts for seven ages on the World stage, but in reverse order, from oldest to youngest, with some key explosive events as the backdrop. It is presented in two parts, converging in Ontario. In Part I we encounter physical-chemical-biological explosions in the abiotic and biotic world. In Part II we implode (focus inward), in hopes of blending our natural world with our community, actions and interactions with others–an implosion of nature and culture, to see what post-play chatter we can initiate.

Now we welcome our principal company of actors: geodiversity, having this basic definition:

Geodiversity is the variety of earth materials, forms and processes that constitute and shape the Earth, either the whole or a specific part of it. Relevant materials include minerals, rocks, sediments, fossils, soils and water. Forms may comprise folds, faults, landforms and other expressions of morphology or relations between units of earth material. Any natural process that continues to act upon, maintain or modify either material or form (for example tectonics, sediment transport, pedogenesis) represents another aspect of geodiversity. However geodiversity is not normally defined to include the likes of landscaping, concrete or other significant human influence.

At this point in our story our world is formed and the stage is set. The stage is suspended in the vastness of space. It’s a place of spectacular beauty, with a slow rotation of players. The audience is in a hushed silence, waiting for the first Act in our diversity play, ready if needed to boo bad actors off the stage…

PART I

Act I – All the World’s a Stage

It took over 9 billion years after the initial explosion, so about 4.6 billion years ago, to get sufficient cosmic dust and rocks to agree with each other enough to form the accretion of a new celestial body, a world we here call Earth (which is one name of many). Here we find the basic building blocks for everything we know and everything we have ever known.

As the world cooled sufficiently, and for billions of years, all the world’s been a stage for a slow but steady rise in geodiversity, with a few exiting the stage, and many others entering. Throughout this time there were numerous explosions, the biggest is believed to be when a Mars-sized planetoid we named Theia crashed into Earth, ejecting the material for the moon. A meteorite is generally considered to be responsible for the Sudbury Nickel Rim–this would have been an explosive event of epic proportions. No doubt there were new minerals formed as a result of these events. But generally speaking, over this vast timescale of billions of years, geodiversity was not particularly explosive.

In a series of studies, Hazen et al (2008), Hazen et al (2017) and Hazen and Morrison (2022) describe geodiversity as a function of mineral diversity. The research identifies that the world stage has hosted between 5,000 and 6,000 minerals, much of it believed to be biologically-mediated (formed as a result of biological processes), even in the early days of world history. The research describes a slow increase over deep time, culminating in the Great Oxidation Event, resulting in a groundswell of new minerals due to the availability of oxygen in the atmosphere to react with other elements (relatively speaking, oxygen is highly reactive and found all sorts of ways to combine with rocks and minerals). But despite this reactivity, throughout this deep time period of billions of years there’s nothing even close to being considered an explosion of geodiversity.

As this first Act comes to a close, we have introduced our main company of actors on our world stage: thousands of minerals and rocks. The explosive events are only heard in the distance, far from our consciousness.

Act II – The Biodiversity Explosion

Our next company of actors is biodiversity. While geodiversity was slowly being introduced to the world, biodiversity was doing a two billion year warm-up off centre stage, creating new mineral assemblages and the basic acting techniques to try on stage later. Biodiversity gained centre stage in the Cambrian Period beginning about 541 million years ago, offering up a spectacular array of biodiversity–a first of its kind event to that point, live on stage, to the audience’s delight–an explosion of life, as it were.

The Cambrian explosion was an unparalleled emergence of organisms between 541 million and approximately 530 million years ago at the beginning of the Cambrian Period. The event was characterized by the appearance of many of the major phyla (between 20 and 35) that make up modern animal life. Many other phyla also evolved during this time, the great majority of which were booed off the stage to become extinct during the following 50 to 100 million years. This explosion was a time of trial and error, triumph and failure including five major extinction events in the Phanerozoic Eon, shaping and reshaping our world (Britannica, 2023).

From the Cambrian explosion until the Anthropocene, biodiversity held centre stage, providing in retrospect endless things to fascinate us, from sea-dwelling mollusks to the first amphibians to dinosaurs to giant mammals to millions of plant types to billions of insects–more than we could imagine. And imagine we do–these are the stories of our communities, stories of triumph, and of failure. We are discovering more stories all the time, and are endlessly fascinated by what we find. If the Cambrian was an explosion, it was also implosion–through the extinction of species, the Cambrian was the first significant reckoning of how actors, even ones that are not “bad,” can be booed off the stage.

During this Act, we swam in the primordial sea to witness the explosion of life. We came to appreciate that the development of life is strongly related to and has a foundation in abiotic conditions, and that geodiversity has been the basis for the increasing biological diversity during geological history. We gained an awareness that actors enter and actors exit, but all have a role in shaping our understanding of the world and we made the first connections to our collective consciousness.

The Cambrian explosion and aftermath is now a time capsule of living memory, creatures and landscapes etched and worn by elemental spectres. Time is bounded by mirrors, inside are an infinite array of shapes and possibilities beyond our own reflections. Within and without time there is a cacophony of deep time chatter of ancient beings, thawed echoes of sounds long ago absorbed by frozen rock. Landscapes wait patiently now for another day, one in which the stewards of the land have listened louder to the wisest of past actors.

Act III – The Geodiversity Explosion

Fast forward to the Anthropocene (our present epoch, if the title is approved), as it hosts a world-first explosion of geodiversity. Hazen’s team continued the mineral identification into the Anthropocene to compare diversity through the ages. The work had a basic hypothesis that once researched they would conclude that the mineral count has roughly doubled since humans have been moving things around–this would be significant. But when they did the review, they were startled to find out that the maelstrom of human ingenuity had increased the number of unique minerals 40-fold, to a whopping 216,000 minerals and counting! Relatively speaking there’s no comparison of mineralization rates in the past.

A small but significant number (about 200) of these newly minted minerals were identified as caused by humans without deliberate manufacturing. The activities that created these include dump fires, mine fires, drill core weathering, shipwrecks, alterations on ore dumps, mine tunnel walls, mine water precipitates, slag, smelters, coal mine dumps, interactions with mine timbers or leaf litter, geothermal piping systems, and new minerals formed in storage cabinets in museums. If you’re thinking that these origins are not glamorous, you’re in good company. But let’s not be hasty to judge.

Even 200 since the industrial age is a phenomenal increase, that’s roughly 1 per year. If that rate were to have been in effect throughout the ages, we’d have billions of minerals, not just thousands. Compared to the past rates, even at its least glamorous, the rate of new actors certainly qualifies as an explosion of geodiversity.

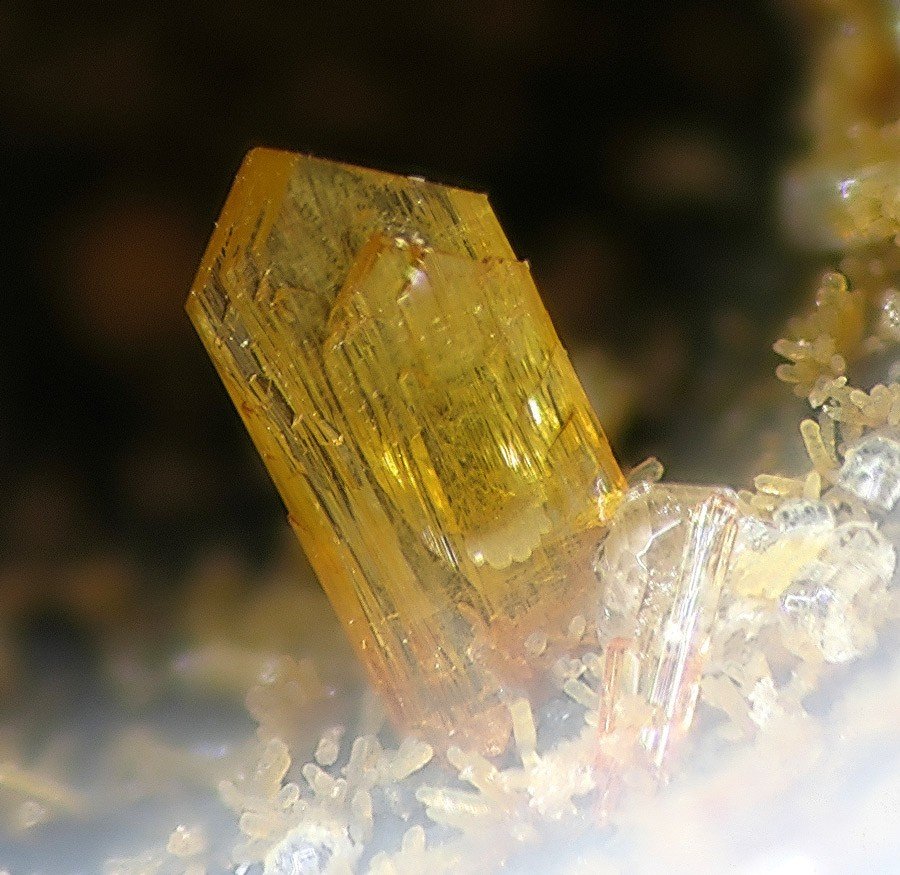

Here is a small sample set of the new actors:

Abhurite. Image by Thomas Witzke, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

Chalconatronite. Image by Leon Hupperichs, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fiedlerite. Image by Christian Rewitzer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Nealite. Image by Christian Rewitzer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Simonkolleite. Image by Henk Smeets – Tomeik Minerals, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Looking beyond minerals, on a larger scale, there is plenty of geodiversity to go around. Altered Earth (Thomas, 2022) describes how an estimated 316 billion tonnes of material has been reworked by humans in the Anthropocene. If ever there was a rock-like substance that characterized human influence it would be concrete, the diversity of concrete types alone is staggering.

An estimated 9 billion tons of the materials reworked by humans is plastic (Thomas, 2022). Plastic is everywhere: found in mines, in dumps, in river sediment, in groundwater, finding its way through subduction zones, etc. A living poster-member of the Anthropocene is Eurythenes plasticus, the name given to a new species found in the Marianas Trench in 2014, named this way to highlight that plastic has reached places we haven’t even explored. Plastic is becoming geology. Case in point, the Plastiglomerate presently on display at the Museum of Nature in Ottawa.

So…entering the stage…Barbidiversity. Now, to avoid copyright infringement, the definition of barbi we’re going with was found in a baby names book and means “Traveler from a foreign land.” Indeed, foreign to nature perhaps, or foreign to Turtle Island. The Anthropocene really is a barbidiverse world, with plastic now a ubiquitous part of the geological record–its plastic, that’s fantastic…right?

It is just a matter of time before geodiversity has an official unintended mineralized member (how about… barbiite) with this dubious distinction, perhaps to be found in a landfill near you.

This explosion of minerals is in sharp contrast with the rapid decline in biodiversity in the past few decades (some say by as much as a 90% decrease, and on this metric this perhaps should be considered the Sixth Extinction event (Leakey and Lewin, 1995).

In this Act, geodiversity has taken centre stage again, meanwhile biodiversity is running for the exits. As we look at this diverse group of new actors with somewhat bizarre origins, we wonder–is the providence (origin) of these new actors (i.e. borne out of our environmental messes, etc.) any less legitimate than others? How inclusive are we being, really? We are all made of the same atoms, just constructed in different ways. The difference really is only in our perspectives and our acceptance. In this Act we begin to see how our “natural” community can be redefined, provided we are open to it.

Act IV – Ontario Geodiversity Takes the Stage

As far as geodiversity goes, Ontario has it all, from ancient Precambrian biologically-mediated banded iron formations to the carbon-storing living peatlands of northern Ontario and everything in between, there are innumerable geodiversity stories to tell. There are stories of explosions, sure, but also of transformations, weaving present time to past. The GeoscienceINFO website is chock-full of guides to diverse geological landscapes in Ontario. I encourage you to check them out. Since I took my first virtual tour I’ve been looking forward to the day I can do it in real time and place. I cannot do these justice here.

As for mineral diversity, while my examination of Hazen’s research revealed a few (nine) new minerals in Canada it did not reveal any new Ontario-specific minerals, but no doubt it will happen sooner or later. After all, Ontario has its share of mines, dumps, drill cores, spills, accidents, a few explosions, and so forth. As a result of all of this activity we probably have a few new minerals in dark places just waiting to be discovered.

With this we lower the curtain on Part I. We have introduced our principal company of actors, geodiversity, and have seen the group grow significantly in the past few decades. With the added diversity we have choices to make on the degree of inclusion, and how to manage the actors, when all the world’s a stage.

~ INTERMISSION ~

PART II

We welcome back our principal company of actors–geodiversity, which as you recall, had this basic definition:

Geodiversity is the variety of earth materials, forms and processes that constitute and shape the Earth, either the whole or a specific part of it. Relevant materials include minerals, rocks, sediments, fossils, soils and water, etc. (see above) …. however geodiversity is not normally defined to include the likes of landscaping, concrete or other significant human influence.

Now, we take the definition further. It still includes rocks, yes, minerals, yes, materials, landforms and processes, yes, but beyond this, geodiversity includes not just the natural world but how we as human actors interact with the natural world: our relationships. So for Part II of our play, we follow the lead of the International Geodiversity Day initiative, with one excerpted definition of geodiversity ringing clearer than the others: “…geodiversity is the foundation of communities, and an intrinsic part of humanity’s relationship with nature.”

We continue our story, picking up in Ontario, where we begin to look inward to connect nature with community.

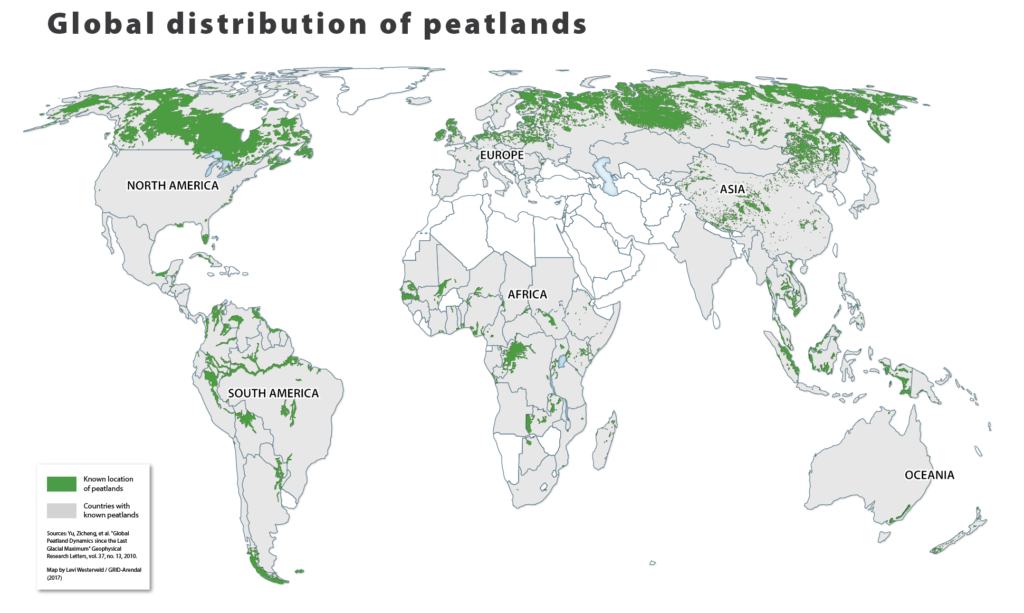

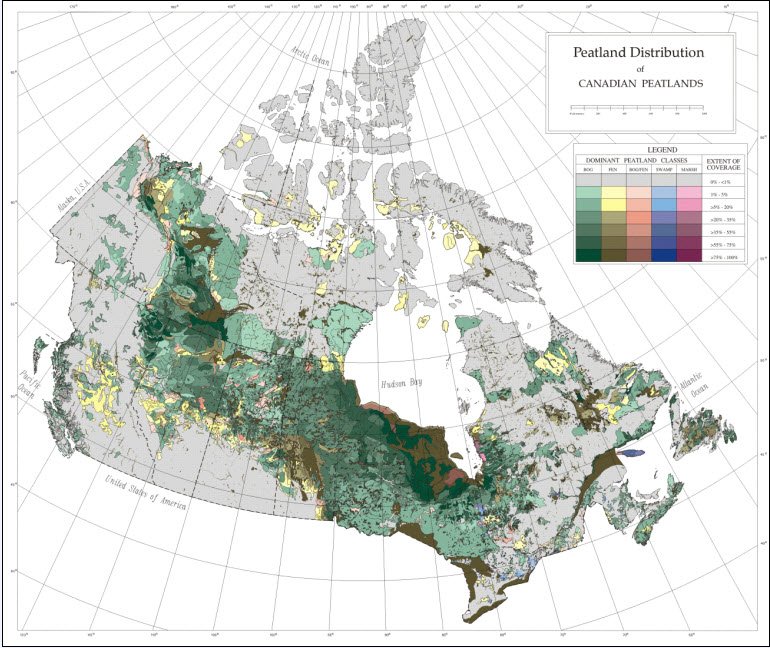

Act V (Ontario geo-communities)

Here we again shine our stage light on living geodiversity, the peatlands of northern Ontario. Even when considered at a worldly scale, it is Ontario that hosts the central part of these peatlands, which may be one of the most underrated actors of the world. These lands are a key biodiversity and geodiversity feature and one of significant cultural value. At a time when carbon sinks are all the rage for the audience, the peatlands, which straddle biodiversity and geodiversity effortlessly, are recognized by only a few as a key actor in carbon storage for the planet. While there is considerable uncertainty in measurements at present, they are believed to be, square metre for square metre, around 5 times more efficient as a carbon sink than the Amazon Rainforest. As shown here, Canada has patches of the highest density and extent of peatlands of anywhere in the world, and Ontario has the most of any province or territory.

From a geodiversity perspective on a worldly scale, there’s nothing quite like them, and they should be handled with care. According to the UN, 80% of the remaining biodiversity in the world is found in areas of Indigenous stewardship (however it is not clear on the percentage of geodiversity). In Canada, Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) have been identified as a potential mechanism to achieve Canada’s biodiversity targets, and by extension, geodiversity. If we want to reach these targets we need to look at our diversity holistically, bringing to bear the actors most connected to the stage, and all of the talent these actors bring. IPCAs appear to be a viable consideration in Ontario and are already being pursued in parts of these lands.

As this Act draws to a close, we introduced Ontario geodiversity (in Part I) and are keeping a watch for new minerals. In Part II we identified that we have some influence on the stage production–we can write some of the script, adjust the lighting, and paint the backdrop. We are developing an awareness that there are more visible actors involved with geodiversity than we previously realized, and our thoughts move from external to internal, from diversity to inclusion.

Act VI – Community and Culture – Putting the Actors Together

The dust and the smoke clears, as we continue to reconcile the unnatural blast of nature’s materials and peoples, reordered to our specifications. Brilliant rays seek to remedy the darkest of places, propagating waves of light to chase out swirling waves hiding in corners. Imagination soars to new heights in clearer skies.

As our earlier Acts have shown, geodiversity involves both nature and community. Scotland, the birthplace for some of the most important modern theories in geology, was earlier than many to recognize the connection of community and geology–they developed a Geodiversity Forum, and produced a Geodiversity Charter in recognition of this special relationship.

Another type of connection between communities and landscapes was recognized in law in 2017, with the Maori and the government of New Zealand. This law recognizes that natural features of the world are “people,” and can have representatives. In 2021, the Muteshekau-shipu (magpie) River in Quebec became the first natural feature in Canada to receive person status. In effect, it merges natural rights and steward responsibilities–the river, through Innu representatives, has nine rights including the right to flow, maintain its biodiversity, and to take legal action. These steps appear to recognize sentience (capacity for feeling or perceiving) of our natural environment–a geo-sentience of our world.

With thoughts such as these, we recognize the tie between the abiotic and biotic worlds and tether them to our cultural landscape. They are the same, we are the same, or should be. If it helps, we’ll anthropomorphize (to ascribe human characteristics to things not human) for a moment, and say that rivers and rocks around us all are people too, or may be soon by law, so we need to think more about inclusion.

In this Act, we begin to implode, that is, to look inward at our relationships and responsibilities to each other, and to nature. The blast of the cultural explosion that was colonialism in the past few hundred years is past its zenith and is to be booed off the stage. We begin to hear nature again and along with it the cultural connections of those in the places of diversity, those that have understood this connection for millennia. As we immerse ourselves in the truth of our history we participate in a kind of implosion therapy. We help find ways to administer medicines to remedy trauma (Note: Doctors in several provinces can now write a prescription for patients to visit nature). Through this inward reflection we find many ways to connect landscapes to culture, taking the lead from those who were here first–the people, and the rivers, and so forth.

“ …this implosion of cultures makes realistic for the first time the age-old vision of a world culture”

Kenneth Keniston

Act VII – Resetting the Stage

The explosion of geodiversity in the Anthropocene has begun with minerals but may end up being an explosion of recognition, that of geo-sentience, and of strengthened bonds of community. This will occur when our precious geological features and interwoven social fabric become part of the roundtable discussions of governing Councils, led by the people and peatlands of northern Ontario and Manitoba, the people and Greenbelt aquifers of the GTA, the people and Niagara Gorge, etc., all with representation and diverse voices of various people, rivers, and landforms at the table.

While it’s unlikely that the recognition of natural features as principal actors will result in an explosion of new actors to the stage, this is a significant opportunity for actors that have been previously shut out. Recognition of natural features as people has some potential to bring together groups of people and landscapes, reconciliation, and bridge different ways of knowing. If the populus allows it, it’s just a matter of time before the interests of key landforms are more fully represented at the boardroom table. Will we be receptive or boo them off the stage?

On related stages, new economic models are being displayed to the public. The Wellness Index (also from New Zealand) is being considered by B.C. as a more sensible economic framework, allowing us to boo outdated economic systems off the stage, and have a chance to exercise real sustainability. And throughout the land, economists are figuring out how to include natural assets in assessments of assets and liabilities–these have started with forests but will inevitably include geoheritage sites and key landforms.

New minerals are a scintillating curiosity, as beautiful as any, and they should be welcomed as legitimate actors. But for some, the Anthropocene Explosion has and continues to be a trauma. This highlights the need for some bad actors to be driven off the stage. Psychology and Indigenous healers identify community and culture as medicines for healing, allowing some to boo trauma off the stage as reconciliation takes shape. There are seven medicines to reconcile psychological wounds for our seven ages: truth, free your heart, community care, self-care, creativity, resistance, and culture.

In terms of diversity, geoscience itself has struggled with human diversity compared to the rest of Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) at present, and is exhibiting declining enrollment. Interest in geoscience will only increase if we encourage people that know how to connect landscapes to geoscience, and for the rest of us find ways to be inclusive of others by unlearning/learning. Increased connections of people to land fit well into Canada’s aspirations for environmental assessment, sustainability, reconciliation and biodiversity, for a start. The geodiversity explosion can lead to implosion, which is a focus inward on our communities, healing and embracing the various new actors. Along the way, those that we want to most connect with will be attracted to geoscience and be active agents of change.

Gaia spoke of the world as interwoven with the genesis of all of life. She spoke of vast deep time cycles of growth, decline, renewal, trials of unsustainable shapes and patterns, many that litter the geological record. She spoke of lands of giants, morphing into new formations, folding back into the earth, to be spat out again in a different form. As Gaia spoke it becomes apparent that the world is not only a refuge for rocks and minerals and life but one of a collective soul of creativity and inspiration that we’re lucky enough to play a part in for awhile. She said the land has rights, and caretakers have responsibilities. When asked whether there was a grand plan, she just laughed…and carried on patiently adjusting the stage lighting.

We have now been through seven Acts, and when combined the ages create a new understanding of the world with a more diverse set of actors. The seven Acts intersect on community and culture, just as do the seven medicines. With the full suite of geodiversity actors we have connected our physical world with our imagination, sometimes surprised at what can be achieved.

As the curtain lowers, we look between the mirrors to contemplate what happens in the post-production, and hope to see continued convergence on community and culture. The Great Anthropocene Explosion has introduced a diverse set of talented actors, intricately connected between nature and communities. Now it remains to see how truly inclusive we will be of these new actors…when all the world’s a stage.

References:

Hazen et al, Mineral evolution. American Mineralogist, Volume 93, pages 1693-1720, 2008

Hazen et al, On the mineralogy of the “Anthropocene Epoch”, American Mineralogist, Volume 102, pages 595-611, 2017

Hazen and Morrison, On the paragenetic modes of minerals: A mineral evolution perspective. American Mineralogist, Volume 107, pages 1262-1287, 2022

Altered Earth, Getting the Anthropocene Right. Cambridge Press (Thomas Ed.) 2022

Paul Hubley is a Professional Geoscientist (P.Geo.), Canadian Risk Manager (CRM), Co-Coordinator (Canada) for the International Association of Promoting Geoethics (IAPG), People and Policies Coordinator for Geology for Sustainable Development (GfGD), Professional Geoscientists Ontario (PGO) Past President. He looks to the day when a river or a mountain is appointed as Chair of the Board.