Excerpted from The Last Speaker of Bear by Lawrence Millman published by Trinity University Press. For more information, please visit tupress.org. Reprinted courtesy of Trinity University Press.

A meteorite 400 feet in diameter whisks through the atmosphere in a fiery flash. Traveling at 20 miles per second, it slams into the earth, sending boulder-sized rocks flying off in all directions as well as excavating a gaping hole in the earth’s crust.

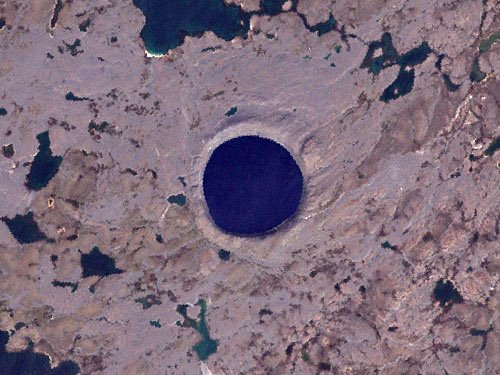

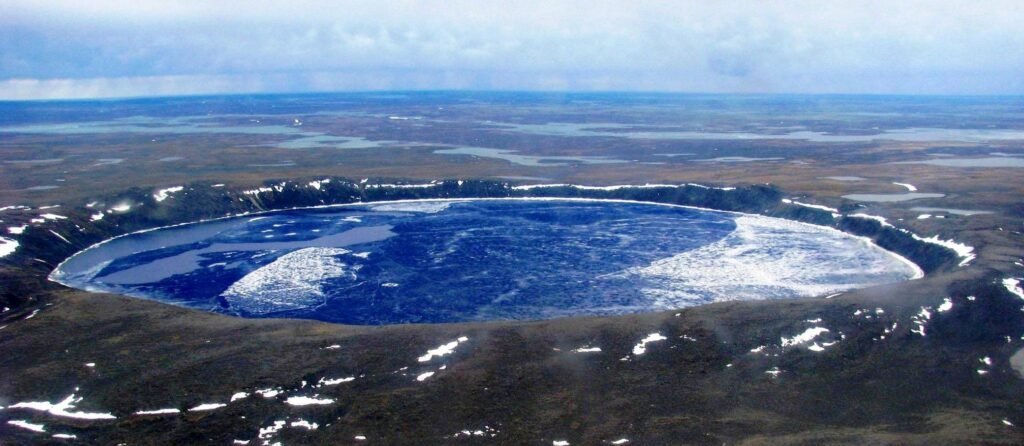

Some 1.4 million years later, I was seated in a Twin Otter aircraft flying over northern Quebec’s Nunavik region and looking out the window at the seemingly endless tundra. Suddenly I saw a perfectly circular blue eye — the meteorite’s crater filled with water. Formerly called Chubb Crater, it now bears the Inuit name Pingualuit, a word that simply means pimple. Being three miles wide, the crater is a rather large pimple.

On landing near the crater, an Inuk named Yaakaa greeted me and showed me where I should pitch my tent. During my visit, I encountered a totally pristine habitat, with none of the broken-down ATVs, candy bar wrappers, or potato chip bags that litter so many other parts of the Canadian North. Apart from a few old Inuit fox traps, there was no evidence that my litter-minded species had spent any time here.

The day after my arrival, Yaakaa and I climbed up the slope cluttered with the granitic boulders that had been ejected by the meteorite’s original impact. Each of these boulders displayed a design created by lichens such as the cartographic Rhizocarpon geographicum and the bright orange Xanthoria elegans.

After little more than an hour, we were standing at the crater’s rim, and I looked down at the huge circular lake that I’d seen from the air. The water was the bluest blue I’d ever seen.

“We call this lake ‘The Crystal Eye of Nunavik,’” Yaakaa said, “and it may have the purest water of any lake in the world.”

We walked around the edge to a spot where the slope down to the lake was the least steep. As we hiked down, the quietude was interrupted by severaI loud maniacal laughs, followed by a sound similar to an explosion.

I wondered: Was the Crystal Eye looking at me, an outsider?

Not at all. The inside of the crater was a giant amphitheater, and its walls amplified any sound inside it. What I heard was a couple of loons chortling at each other and diving for fish. The splashes from their dives were the explosions.

When we reached the bottom, I cupped my hands in the lake, then raised them to my mouth. I tasted a rich, full flavour that made all the other water I’d ever tasted seem tacky as well as downright dull.

As we were hiking back up to the rim, I could still hear the loons screaming wahoo! quarpp! wahoo wahoo! Since loons are among the very last birds to migrate south for the winter, they would probably be screaming in this fashion right up until the time the lake froze.

When we reached the top of the crater, and before heading down the other side, I stared one last time at the remarkable blue eye that seemed to be staring directly at me.

The Last Speaker of Bear © 2022 Lawrence Millman

Author-explorer-mycologist Lawrence Millman is the author of 19 books, including such titles as Last Places, Northern Latitudes, Fungipedia, A Kayak Full of Ghosts, Hiking to Siberia, and — forthcoming — The Last Speaker of Bear. His compass invariably points North; he has made more than 35 trips and expeditions to the North, but he’s never been to Rome. As a mycologist, he found a fungus in 2006 that had been declared extinct in 1909. He keeps a post office box in Cambridge, MA, USA.