It is common to hear stories of highly gifted individuals pursuing a career path and ultimately landing their dream job after years of climbing the ladder. Sometimes I even tell people that I am very lucky to have landed my dream job. “Lucky” is certainly true, but the fact is, I’m not particularly gifted, nor did I imagine working in the career I have now, that is, being an educator. That sort of happened by accident. My job is amazing, but my work does not quite match what I originally envisioned. Yes, I have always wanted to be a paleontologist, and yes, people call me a paleontologist, but my main passion is teaching geology (and not much of it is actually paleontology). When people asked me what I did for a living, I used to reply that I was a paleontologist. Now, I’m more inclined to say that I’m a university teacher.

I guess I am getting to that age where I wake up and think, “Well, how did I get here?”” (and now I’m cursing David Byrne because I know I’ll have that certain song in my head for the rest of the day). I am slightly bothered by the fact that I was born in 1966. This means I’m about as old as the theory of plate tectonics. I have only recently come to fully embrace this without the eye twitch! Plot it on the geologic time scale and it doesn’t look quite so bad. But I digress…

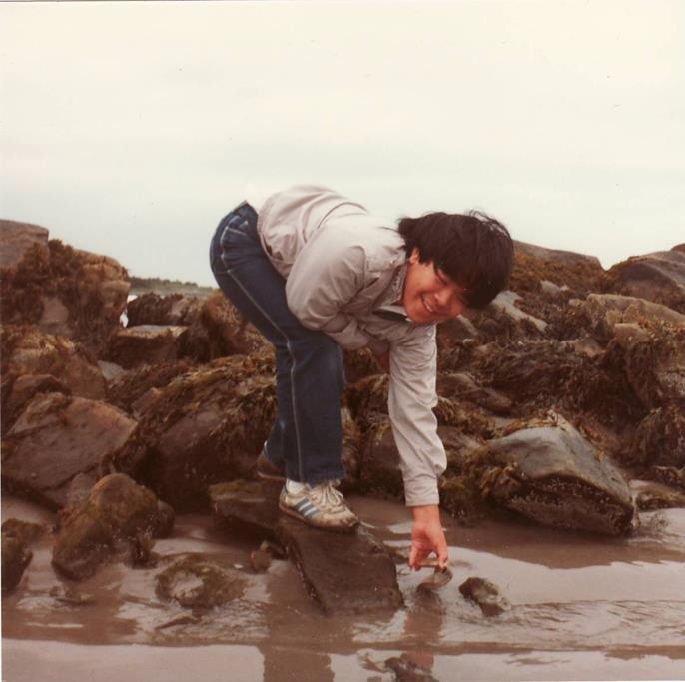

I was born in the town of Olds, Alberta. My earliest memory of a rock that interested me was a piece of shale that a friend of the family showed me. It had a trilobite in it. Apparently, I had already shown an interest in rocks at this point, and she thought I might be interested in looking at it. I remember seeing it and thinking that it was the coolest thing I had ever seen. It looked kind of creepy, but beautiful at the same time. And a dead animal in a rock? Sign me up! I’ve noticed that a disproportionate number of photos I have of me as a kid show me looking at the ground for fossils (or rocks). I don’t know exactly what drew me to fossils and rocks. Maybe it has something to do with always having been vertically challenged (and being so close to the ground)? Or maybe it’s an obsession with dead things? I still don’t know exactly what it was…

This obsession with fossils got me in trouble at times. I remember my mom being very upset with me for being nearly hit by a train while looking at the stones in the ballast of the train tracks. I was nearly hit by a car once when I was inspecting gravel on the side of the road too. I was developing an interest in dinosaurs as my parents would take me to Drumheller (about an hour and a half drive from Olds) to look for dinosaur fossils (the Royal Tyrrell Museum wasn’t yet constructed). Then my dad (a professor in horticulture) got a job at the University of Guelph. In Ontario. Well, dang – there goes dinosaur hunting. Fortunately, I found out that there were a lot of old invertebrate fossils to be found in Ontario. I started finding fossils in…driveway gravel (of course). I was very, very fortunate to have parents who were supportive of my strange interests.

My fossil obsession continued through my teen years. I kept it hidden from most others, as I thought most people would think it was a really weird thing (but who are we kidding? Teens think everything is weird). One thing I did discover during high school is I always learned more about something if I had to explain it to someone else. This still holds true for me today. There are a whole lot of things I wouldn’t know now if I didn’t have to teach about them in my courses.

The fantasy of becoming a paleontologist sat in the back of my mind for years. But I had always assumed that I would have to be an exceptional student to get into that sort of field. The thing was, I was not an exceptional student. Especially in science. And I was hopeless at math (and I’m still hopeless at math). My teachers in high school (and my guidance counsellor) told me that if I was to go to university after high school, my best bet would be visual art, music or maybe English. I don’t think any of them expected me to go into science. My grades, although definitely not stellar, were good enough to get me into the University of Western Ontario for science, and ultimately into the geology program.

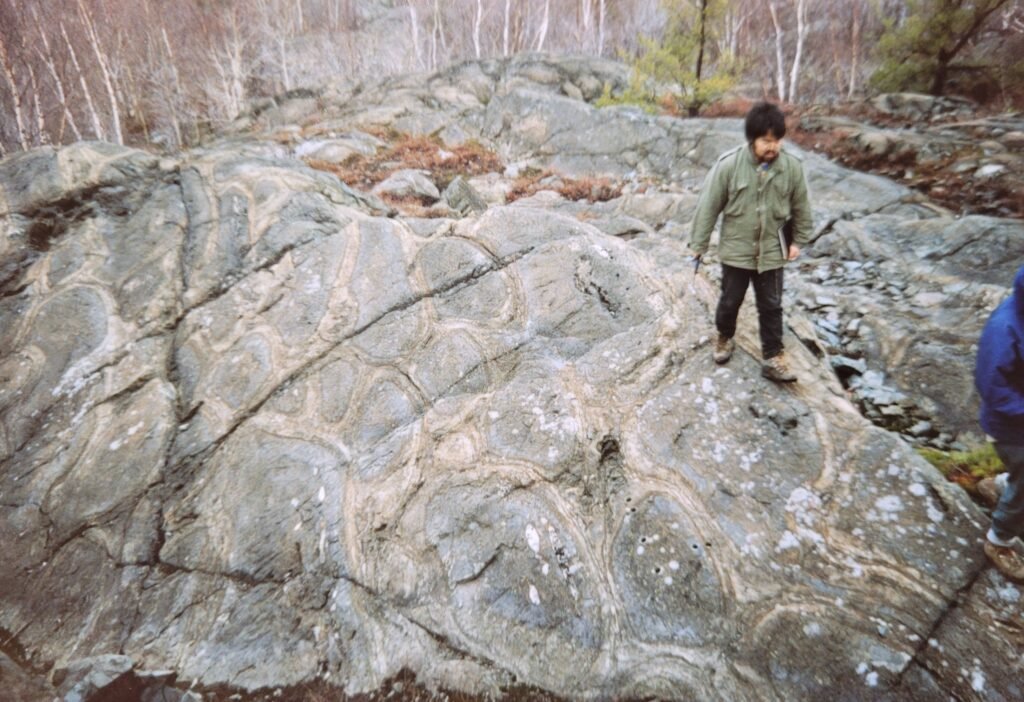

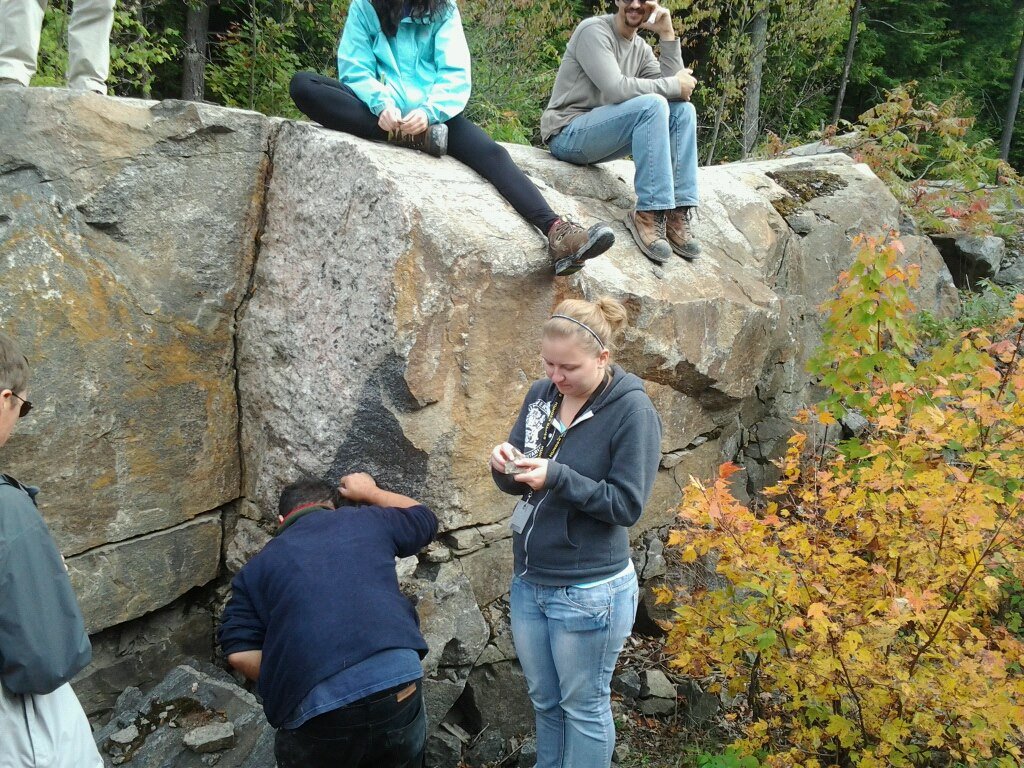

By the second year of my undergraduate program, I found my people. I became friends with other students interested in geology and was delighted to learn that a lot of my peers really sucked at math too. One of the most transformative realizations I came to appreciate from the courses I took was that paleontology was part of something much bigger than I formerly realized. Taking courses in a variety of subdisciplines – sedimentology, geochemistry, structural geology, petrology, and many others – made me appreciate the complexity and interconnectedness of natural processes in the Earth system as a whole. The idea that (in conjunction with characteristics of the rocks that contained them) fossils could be used to interpret past environments just blew my mind. And gaining the ability to visualize, in my minds eye, how a given rock formed (something I often to refer to as “looking beyond the rock”) felt like acquiring a superpower. So, while I came to my undergraduate degree wanting to study fossils, I left with a deeper appreciation of rocks – the context for fossils. So, l kept looking down, but my view of the ground became much, much bigger.

From my undergraduate degree at Western, I went to McMaster University to do graduate work, which began as a Master’s project, but evolved into a much larger Ph.D. project. With my newfound appreciation of the interdisciplinary nature of geology, I sought to figure out the life habits of ammonoids (those squiddy-looking fossils with a shell) by combining fossil occurrences with observations on features of the rocks, some geochemistry, and (gasp) even a few mathematical tools (to figure out shell strength). These were the same fossils I used to collect and that I fantasized about studying when I was a little kid. I had to laugh at myself because, in spite of being a little taller (although not by much), I probably still looked like that little kid looking at the ground.

This is where my master plan took an abrupt turn. When I said I wanted to be a paleontologist, I had assumed that I would a researcher. That’s basically what I was trained to do – paleontological research. Part of doing a graduate degree is to be employed as a teaching assistant (TA). My TA duties centred on assisting in labs for various courses. While I was obviously committed to writing my Ph.D. dissertation, I discovered that the joy I experienced in teaching greatly outweighed the joy of doing research. Once I completed my Ph.D. stint, I was fortunate to be hired at Western as an instructor (and outreach coordinator), so I was able to develop my skills as a teacher.

The fact that I am in any way capable of teaching a class of sometimes hundreds of undergraduate students still boggles my mind. You see, even now, I am a textbook introvert. I tend to avoid people. I’m painfully shy. If I’m invited to a social event, I’ll probably make it awkward. And as you might expect, I get really bad stage fright. But here we are. This is what I do, and I can’t think of anything else I would rather be doing job-wise.

So how have I been able to teach so many students in so many courses over the past 25+ years when I am so socially awkward? I don’t have a definitive answer to this, but I suspect that, for whatever reason, I find my “happy place” when I’m in front of a class. I know this feeling well. It’s the same feeling I experienced when I was a TA during my graduate studies. It’s the same feeling I had when my eyes opened to a whole new world when I was an undergraduate. And it’s the same feeling I had when I saw that first trilobite at four years old. It’s a feeling of wonder that just has to be shared. Geo-evangelism, if you will.

As a university instructor, I am rewarded by observing students become actually excited about learning about geology. Most of the students I see are not in a science program. Most dread having to take a science course at all. I can see the fear in their eyes. By the end of the course, many of these very same students admit that science isn’t so bad and that they have actually learned some really interesting stuff. This is what keeps me doing what I do.

Today, I liken my childhood vision of what I wanted to do when I grew up to a 1950s version of the year 2022. That vision sort of materialized, but not exactly in the form I expected it to. I never would have expected to have found my calling in teaching, but that’s ok. Life can be weird that way.

Cam Tsujita is an Associate Professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at Western University and a 3M National Teaching Fellow. He received his B.Sc. (Hons.) in Geology at the University of Western Ontario, and Ph.D. in Geology at McMaster University. His research focuses on the paleoecology, taphonomy and shell architecture of invertebrates, particularly fossil cephalopods. He is teaches a variety of first- and second-year undergraduate courses in physical geology, paleontology and evolution, and connections between geosciences, culture and art. He also coordinates public outreach events and learning activities with local primary and secondary schools.