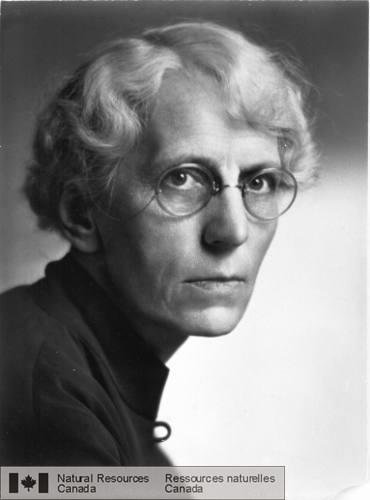

Dr. Alice Wilson, born August 1881, was one of Canada’s first female geologists, and the first female to be hired to work as a geologist at the Geological Survey of Canada. She persevered in the face of many personal and career-related challenges and paved a new path for women in geology in Canada.

Alice Wilson grew up in a family that respected and encouraged education and exploration. She spent many summers canoeing, kayaking, and exploring the land and water around her family’s cottage in Ontario. Her father was a professor of Classics at the University of Toronto and both her brothers received PhD’s in their respective fields. When Alice was 20, she decided to study Classics at Victoria College in Toronto, with the goal of becoming a teacher. It’s unclear whether Alice actually wanted to pursue teaching or whether she did this because it was expected of her at the time. According to her friend Winston Sinclair, Alice said that in her youth teaching was the only acceptable field for a young lady. Perhaps this is why she decided to become a teacher.

Her career path took a twist in her last year of university when she became very ill with anemia. She was unable to complete her courses and dropped out of school. After a few years in recovery, she started working in 1907 as a clerk at the University of Toronto. She had collected fossils as a child from the Cobourg Limestones near her home and was already passionate about palaeontology. In 1909 she became a museum assistant in the palaeontology department of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC).

In 1911, she finished her degree in Classics and was hired full time at the GSC. During this time, she connected with Percy Raymond who was the Chief Palaeontologist at the GSC. Her knowledge of languages came in handy when Percy needed her to translate a textbook of palaeontology from German to English. Percy connected with Alice and encouraged her to take a leave from the GSC in order to pursue a doctorate degree. Alice applied to take a paid leave in 1915 but she was rejected, despite the fact that other male geologists who applied for the same leave were granted it. Meadowcroft wrote that Alice believed her rejection was based solely on her gender, since the “fundamental reason [for rejection] has been that it would make a woman eligible for the highest positions in the Survey” (Meadowcroft, 1990, p. 208).

While she continued to apply for approval, Alice and Percy published an article on a new species of brachiopod. Unfortunately, when Percy left the GSC, Wilson’s other colleagues were not as eager to include her in their publications, and she was forced to work alone. In 1916, she paid for her own trip to Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, NY to study comparative anatomy and marine biology for six weeks.

When she returned to Canada in 1916, Wilson decided to help in the war effort for World War I. She joined the Canadian Women’s Army Corps (CWAC), an all-female military unit providing aid to the Canadian troops as decoders, drivers, cooks, stenographers, telephone operators and many other positions. The CWAC’s wore uniforms with a badge of three joined maple leaves, and on the collar of every uniform was an image of the helmeted head of Athene– the Goddess of War. As a willing volunteer for the CWAC, it is clear that Wilson didn’t shy away from danger or hard work. Women in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps were often subjected to disdain and discrimination from the Canadian public. General sentiment at the time was that women should be in the home, not in the army, and many people thought that women who joined the CWAC were of low moral standing. Wilson likely had to deal with some of this discrimination while serving with the CWAC.

Once the war was over, Alice Wilson returned to her position at the Geological Survey of Canada and continued to apply for leave to pursue further education. In 1926, she was awarded a scholarship by the Canadian Federation of University Women (CFUW) to fund her education leave. But even with the scholarship, the GSC still denied her leave. The CFUW lobbied for Alice, protesting her denied leave and demanding the GSC let her finish her education. The GSC finally relented and Wilson left to get her doctorate in geology at the University of Chicago. It had taken more than 10 years, but finally she received the education that she wanted.

When she returned to the Geological Survey of Canada, she was required to switch her area of research from Ordovician to Devonian rocks, due to the demand for petroleum in Western Canada. It was the Great Depression, and any research that could help Canada’s economy was prioritized. During this time, Dr. Wilson was responsible for ordering the National Type Collection of fossils, which is still an internationally recognized collection for fossil specimens.

As she got older, Alice’s research started gaining recognition. She was the first woman to be elected as a Fellow at the Royal Society of Canada and the second woman to be a Fellow at the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. She received many other notable achievements, one of which was the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 1935. The GSC, becoming more aware of Wilson’s achievements, promoted her to Assistant Geologist after she received the MBE. This designation should have been automatically given when she received her PhD 7 years earlier. But this wasn’t what Wilson wanted. She requested to be upgraded to Associate Palaeontologist, a title that she was never awarded throughout her career. Additionally, it wasn’t until 1945– nearly 16 years after she received her PhD– that her colleagues finally started referring to her as “Doctor”.

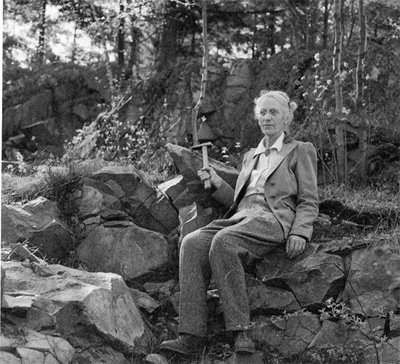

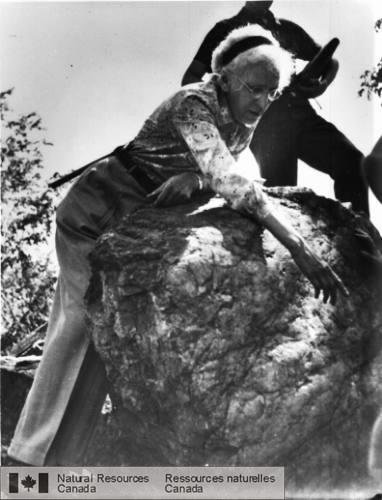

During her time at the GSC, it would have been considered very indecent for a woman to join men on field work. So, she did her research by foot and by bike around her house in the St. Lawrence lowlands. At the time this was a relatively unstudied geologic area, and Dr. Wilson’s research on the geology and fossils of the area was significant in creating an understanding of the geology of the area. Although other members of the GSC were provided cars to get to their field work, the GSC wouldn’t give Wilson a vehicle, so she saved up money and bought her own, driving by herself to complete field work.

She wasn’t always alone, however, and she once took a young teacher Madeleine Fritz with her on a fossil hunting expedition. Madeleine recalled that the research trip changed the course of her life. She later said that “we saw nobody for six weeks except for the occasional Indian or fisherman.” She said that they lived in the wild and had many “hairy experiences” (Meadowcroft, 1990, p 210). Madeleine was so inspired by Alice that she decided to study palaeontology and got her PhD a few years later from the University of Toronto.

Although Dr. Wilson faced many challenges throughout her life, she had a calm and persistent attitude. When asked about gender equality in her profession, she said: “If you meet a stone wall you don’t pit yourself against it, you go around it and find a weakness. And as with other problems, when you look at it in these terms, then you don’t get so personally involved” (Meadowcroft, 1990, p 219). Other people said of Wilson that she never spoke a harsh word and was both charming and gracious. Her friend Winston Sinclair once wrote: “There was no trace of pretension or solemnity in her, and a wonderfully sly sense of humour made her a delightful, if often unpredictable, person” (Sarjeant, 1993, p 125).

Dr. Wilson did have many privileges as a white upper class woman who was encouraged by her family to pursue education and supported by them. But she also faced many challenges from a system that was designed for male geologists. The men around her constantly underestimated her and those in power didn’t provide her with the same opportunities as her male colleagues. Despite this, she authored 50 scientific papers and created reference maps for over 14 000 km2 of the Ottawa-St. Lawrence Lowlands where she lived (Parks Canada). These detailed maps were also linked to descriptions of the geology and fossils of the area. The typological collection of invertebrate fossils that she created during the Great Depression is still used globally as a reference base.

When Dr. Wilson was forced to retire at age 65, as was required by law at the time, it’s said that five people were hired to do the work that she was doing when she left. But despite retiring, she kept doing some work at the GSC without pay. She had quite the sense of adventure and during her retirement she travelled to Brazil to visit the Amazon jungle and Mexico to participate in the International Geological Congress. She started lecturing at Carleton University and gained an honorary doctor of laws from Carleton. She also published a memoir on the geology of the St. Lawrence Lowlands and a textbook about geology for children, called The Earth Beneath Our Feet. The book for children is a sweet and interesting story about three kids asking a geologist different questions about the Earth starting with: “Why do some rocks skip on water better than others?” Dr. Wilson once said that “The earth touches every life. Everyone should receive some understanding of it” (Massive Science). This explains her passion for teaching others about geology and the admiration she gained from her students at Carleton who knew her affectionately as the “rock doctor.”

Dr. Alice Wilson died in 1964 at age 83, having only given up her office at the GSC a few months prior. Her work on the St. Lawrence Lowlands was transformational for our geological understanding of the area. Dr. Wilson paved a path for females to pursue geology as a career. She shared her love of rocks and fossils through her teaching, writings, and research, and was inspiring in her passion and perseverance.

Sources and Further Reading:

Alice Wilson’s Book: The Earth Beneath Our Feet

The Canadian Encyclopedia: Alice Wilson

History of Earth Sciences Society: Alice Wilson

The Canadian Women’s Army Corps

Women in the Geosciences in Canada and the United States

Parks Canada Backgrounder: Alice Wilson

Photos: All photos are from Natural Resources Canada used under the Open Government Licence- Canada.

AUTHOR: Veronica Klassen is the Manager of the Foundation’s blog – Beneath Your Feet: A Geoscience Blog. She studied Arts and Science at McMaster University with a minor in Earth Science and has a masters in Science Communication from Laurentian University. She is passionate about making science accessible and engaging to the public.